“As detestable as they may be, invasive plants such as Japanese knotweed are plants, not barrels of toxic chemicals1.”

– Laidback Gardner

Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is an Eastern Asian invasive species introduced to North American agriculture and horticulture in the 19th century. These red-stemmed and oftentimes large-growing herbaceous plants have fully integrated themselves into American soil, crop life, and garden environments. Japanese Knotweed (or knotweed for short-handed sake) spreads its root system below ground and often outcompetes native species, making it harmful for local or established ecosystems. These plants also decrease soil composition, which leads to worsening structural integrity of buildings and roads. In Vermont, knotweed is placed in the state’s noxious weed quarantine rule list—meaning the possession, cultivation, and sale of the plant is prohibited2. Knotweed lowers agriculture and crop yields by its sheer presence; lowers biodiversity in native regions; and works directly against the stability of our homes. In this article we hope you can learn more about the invasive species found in most back yards, along with the safe and efficient practices of removal it.

Identifying Knotweed

Soil Habitat

To better understand knotweed growth, it’s best to take a soil-based approach. For most plants, nutrient and water availability are very important in determining the environment it succeeds in. This is the first point where knotweed differs from the typical perennial. Knotweed is a species with strong environmental independence, meaning it can thrive in most spaces. That being said, the major environmental requirement of knotweed is seasonal wetness (riparian strips)—riverbank floods, rainy seasons, or valleys are some examples. It is very important to recognize that, despite this, knotweed can be found in most ecosystems, even acidic mine spoils and saline soils found near interstate highways3.

The Stem

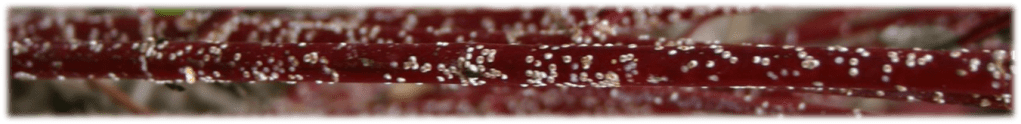

In young, emerging knotweed plants, the shoot (stem) region will appear purplish green. Knotweed is an herbaceous perennial4, meaning it goes through full growth every year. Typically, the plant starts growing in early spring and is tallest in mid-June to July, flowering within the following 2 months. In mid-June to July, the tallest knotweed groups tower at 20ft tall! During its early to mid-growth, the stem changes from purple to green as the plant matures. Later in the season, the more reddish-brown the stem will appear. It’s best to tackle most treatments before the red colored stem appears, as the color signifies the germinating period, when seeds are produced (a nuance we will cover later). The stem of Japanese knotweed closely resembles bamboo but lacks the grass-like leaves (bamboo is a grass, not an herbaceous perennial!). Broken knotweed stems remain vegetatively active for several days once detached, suggesting further care when dealing with knotweed on your property.

Leaves and Flowers

Knotweed leaves can grow from 2 inches in length to well above a foot! (in sister species Giant knotweed, Fallopia sachalinensis). In all knotweed species, the leaves are oval with pointed tips, with a darker leaf side facing the sun compared to the lighter under region. The leaves grow in a zigzag pattern, alternating between sides of the stem. If the plant you’re examining has multiple leaves off the same lateral stem5, it’s not knotweed!

Due to their reproductive nature, this plant is prone to hybridization6, making identification based from leaf form to be a bit tricky. One aspect consistent with most knotweed species are small red dots on the leaf, which tend to be more visible later in the season when the stem is also red. Our suggestion is to focus on shape and ask yourself the following questions—

- Does the leaf have an oval shape?

- Is the leaf tip tapered to a point?

- Alternating zigzag leaves?

- Are there red dots on the leaves (July/August)?

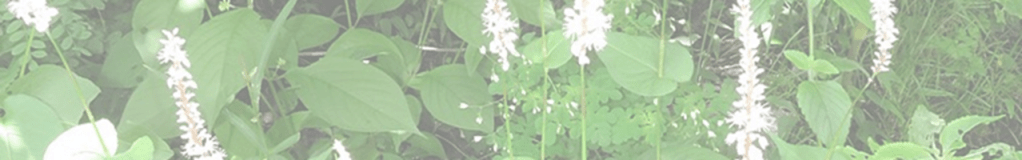

Knotweed flowers appear greenish white, with branched clusters growing at the end of the stems. Some knotweed flowers appear with purple tints and typically grow in regions 4-6 inches in length. The flowers have a pleasant aromatic scent! As mentioned, knotweed with flowers typically means that the plant is in germination, but don’t let it discourage you from any efforts in removal.

Seeds and Roots

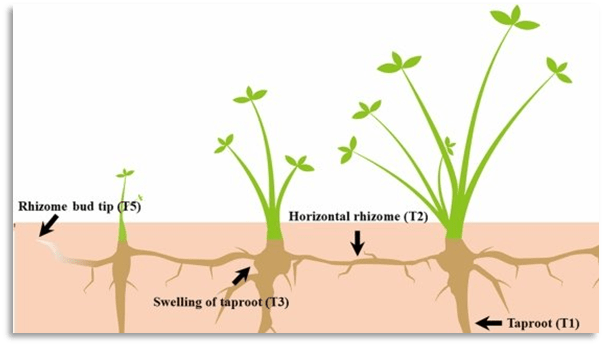

In its native habitat, knotweed reproduces through seed dispersal. But, in most cases in the United States and other non-native parts of the world, the plant does not use seed dispersal as it’s primary way of reproduction. This brings us to the pivotal moment in knotweed understanding—knotweed is a clonal species7. This means that in your local patch of knotweed, maybe in your back yard, garden, or down by the road, these “plants” are altogether a larger knotweed… singular. How does this work? Well, knotweed vegetative growth is unique due to this clonal aspect, but we can explain it briefly through its main steps—

- A mature knotweed (taproot) sends out a horizontal root segment called a rhizome8.

- This rhizome grows laterally, breaking down soil and pushing through new, local nutrients.

- Bundles of hormones build up on regions of the rhizome.

- Eventually, a new shoot tip will emerge from this region and push through the soil

- A new knotweed stem is grown, and the rhizome continues to extend.

Clonal reproduction could be its own blog post, and if you’re interested in learning more you can check out this source on clonal vegetation. The large root systems that exist under most knotweed plots are largely due to the clonal nature of reproduction.

Being able to understand the clonal reproduction of knotweed will help us better grasp the importance of addressing the root system in most treatments.

It’s just because it’s so vast! Knotweed rhizomes can grow for upwards of 100 feet and 15 feet deep, allowing the system to fully take over local microhabitats. Additionally, if left unmediated, these root systems have been observed to expand for over 20 years, even with the addition of local herbicides9. When identifying knotweed root, look for horizontally growing roots that are about the diameter of your thumb—these rhizomes may also have a carrot-orange color reflective of its pigment.

Noticing Dormancy

Knotweed rhizomes allow for extended dormancy—when the plant can survive for long periods of time without sun exposure. This brings the question of how can we identify knotweed if it’s fully below ground? The answer lies in recognition. Knotweed is above ground from early spring to late summer, when its shoots die off and go into dormancy for most of fall and winter. The best practice in dormancy recognition starts the previous season. Once a knotweed species has gone dormant, it will not expand or grow to a point where it’s unrecognizable the next year. Rather, it will resume growth when it has adequate sun availability. So, find your plots early and note where they are… they won’t change.

Why Knotweed Matters

Japanese knotweed isn’t just another persistent weed—it is one of the most ecologically detrimental plants in Vermont and much of the world. Anywhere that knotweed is found, there is likely a small handful of native plants being outcompeted and forced into local extinction. If we can learn to treat knotweed in a way best fit for our environment, we will improve biodiversity of not just local plants but other animals and critters that are reliant on them.

Ecological

Knotweed, once connected by well-established rhizomes, grow in dense regions that tower over 20ft tall. The large thickets formed block sunlight from many local plant species—wildflowers, shrubs, developing trees, and grasses. If prolonged, this leads to the overall loss in plant diversity and potentially induces trophic cascades10…

- Loss in local biodiversity

- Pollinators lose foraging habitat and shelter

- Soil organisms decline as leaf litter patterns change

- Decrease in wildlife nutrition

- Predator-prey imbalance

If left unchecked, knotweed will destroy your local environment.

We have been skirting around the result of knotweed invasion. A monoculture is when the environment consists of a single, exclusive species. Monoculture lacks diversity, migration, and contributes little to neighboring ecosystems. To maintain an environmentally active environment, knotweed should be treated as the real issue it is.

In the intermittently wet environments that knotweed likes to grow, soil health is a real issue. We see this consistently in riverbanks. Knotweed is a relatively shallow-rooted plant. 20 ft deep is not significant compared to other herbacious plants in these areas like dogwoods or willows. Riverbanks with knotweed are less stable to mechanical stress. A river flood, for example, might cause slumping, soil and sediment erosion, and increased turbidity11 in aquatic environments.

Infrastructural and Agricultural

Knotweed doesn’t directly “break” buildings. It’s not strong enough for that. What it is strong enough for is exploiting structural weaknesses. Oftentimes, knotweed rhizomes can push through cracks in concrete, foundations, retaining walls, and floorboards. Like any other plant, knotweed’s biological imperative is to reach sunlight, and it will break things to do so. From a landowners perspective, catching knotweed early on is a gift. Without this, many property owners are left with extenuating costs in the treatment of this tricky plant. Once established, knotweed can lead to several issues from this perspective—

- Increased labor and contracting costs

- Ongoing monitoring

- Lower land usability

Naturally, this creates issues for agriculture and garden settings. Knotweed rarely colonizes active crop fields, but it won’t hesitate to approach field edges or regions of fallow. Once established, the knotweed will only grow and create unneeded competition to local crop, grass, or your backyard garden. Knotweed also hoards space and will make it hard for field accessibility on farms and more noticeable effects in your backyard. As mentioned, a single rhizome can reproduce independent of any stem connection, making these plants hard to eradicate.

Treating Knotweed

Where to Start?

Managing Japanese knotweed often requires the knowledge that all knotweed treatments wont work for your specific case. Due to the plants unique growth system, it often requires years of consistent and timed treatment to accurately address the vast network. The goal of this section is to provide an overview of the different methods you may choose in knotweed treatment, and to give some guidance in selecting your own.

Mechanical Treatment

This approach tries to physically damage and eradicate the knotweed stems, roots, and rhizomes. The strategy is usually central to repeated cutting, mowing, digging, and covering the biomass with hopes of stanching future growth. This method is labor-intensive and must be repeated several times across seasons to be truly effective. Mechanical control is best for—

- Early detected regions of knotweed

- Most urban sites where herbicide is not allowed or discouraged

- Pre-treatment strategy

Chemical Treatment

This treatment uses herbicides in the knotweed environments that become integrated (either absorbed directly or indirectly) to the plant tissue. This treatment is contingent on timing, as nutrient flow within the plant must be downward, toward the rhizome, for full efficacy. Chemical control is best for—

- Large or dense infestations

- Areas where large ecological death are permitted

Integrated Treatment

The integrated approach combines both mechanical and chemical methods over several years. The thought process behind this approach is that mechanical and chemical treatment both have their strengths and weaknesses, with this method aiming to work with them both simultaneously. Oftentimes, integrated approaches can be the best choice as they work better with the perennial environment. The integrated treatment is used commonly for—

- Complex or persistent infestations

- Long-term lower-footprint restoration projects

- Community or municipal projects

Emerging Treatments

Knotweed treatment is an area of active research, and there are many new methods emerging that are trying to address the issue. These strategies often involve more drastic or unconventional methods, making them slightly less accessible to the homeowner. In industry however, these methods may be advantageous, with some forms using biocontrol12 and other nature-based means.

Why Single Treatments Never Work

Before we go more in depth into some knotweed treatment, it’s important to note something that all the options share—consistent treatment. A single treatment approach may rid the area of knotweed for a few months, a season, but it will do a poor job of keeping the environment free of knotweed in the future. It’s written in knotweeds clonal nature. Single treatments won’t address the true extent of knotweed rhizome growth, as they will continue to grow after the initial treatment. As mentioned, these systems can lay dormant, furthermore the reason to be consistent in your treatment. So, as we discuss treatments, be ready to strap into the year-long ride that is knotweed treatment.

Mechanical Treatment

Mechanical treatment is the most accessible form of knotweed treatment, and is one encouraged by many experts, with a relatively low ecological impact when done correctly. When done incorrectly, mechanical treatment can introduce further knotweed biomass to the environment and sustain growth13. It’s important to understand your own commitment level and environmental capacity when deciding to pursue mechanical treatment means.

Cutting Schedules

Studies have shown that periodic cutting has decreased knotweed growth potential from 100% to 5% in three years14. From the same group, a decrease in time between knotweed removal had a positive relationship with the same regrowth metric.

This means that the more often you cut these plants, the less they come back.

Cutting is possibly the easiest way to treat knotweed. All that’s needed is a sharp tool to cut the plant stem section. We suggest cutting the plants 1-2 inches above ground level, eliminating the plant’s ability to photosynthesize and forcing rhizomes to produce new shoots. To take advantage of this, cut every 1-2 weeks during the season, being consistent to cut 100% of shoots emerging. It’s important to use clean tools and to dispose of the cut plant material in a region lacking soil access. This means do not compost the knotweed once it is cut. We’ve found that resting the knotweed stems on a high-hanging branch for 3-5 days allows them to be composted. This process should be maintained each growing season of the following 3-5 years for the best results.

Excavation

Manually digging up knotweed can be a strong treatment for smaller patches, as it requires greater physical demands. Excavation is a commercially offered treatment of knotweed15 and has nuance within its methods. Commercial excavation involves large machinery that pull up all the knotweed biomass, remove it, filter it, and return the soil to the environment. A drawback of this method is that it doesn’t discriminate between native and nonnative plants. This means that any local species, roots, and biomass will also be removed from the soil lifted out of the ground. A benefit of this method is that oftentimes commercial removal business can offer different levels of treatment. For example, a less intrusive form of commercial excavation might only dig up 5 feet of soil mass opposed to 10-15 feet. In all commercial cases, it is hard to preserve the land for agricultural use and is most often used in areas with proposed infrastructure goals.

Excavation can also be a manual process and is one we’ve used right here in Vermont. Manual excavation involves removing most of the rhizome and stem sections of the plant periodically, on a similar schedule to the cutting method. We’ve found most success using root assassin shovels16 to approach the knotweed rhizome. By wiggling the shovels around while simultaneously pulling the lower stem, one can individually excavate the knotweed. We suggest excavating the knotweed monthly every year for 3-5 years to see the best results.

Solarization

This is the process of literally preventing a region of biomass from sunlight. This is often a practical solution to the treatment problem, as it’s less strenuous and uses simple materials. For local treatment a tarp can be used to cover the area, and for larger or more complete removal, geomembrane17 is suggested. It is best practice to solarize with the following steps.

- Eradicate knotweed plot 1 month into the growing season

- Assure soil is damp

- Extend geomembrane or tarp across entire plot region

- Anchor the material with sandbags or something heavy

- Leave in place for 3-5 years

- Monitor edges*

*The most important part of this treatment is to make sure that no lateral growth is established. It’s suggested that one checks on the tarp edges every month of the growing season, similar to how you would with manual excavation. Solarization also rids the soil of any microbes or other plant life, meaning that this method should only be done with long-term rehabilitation efforts in mind.

Mowing

Mowing may seem like an easy solution to the knotweed problem. It’s easy to think that through consistent mowing, knotweed can be fully removed. Yet, in knotweeds physiology, mowing seems to primarily aid growth. By cutting the plant into smaller pieces, you allow these small regions of vegetatively active knotweed to spread further. And with no means of removing these fragments, they are left to grow, often reconnecting with the rhizome sections.

It is due to this that mowing is not a standard or approved mode of Japanese knotweed removal.

Although, there are some exceptions that we’d entertain for the few cased that apply to. Mowing can be used for knotweed removal when the following conditions are met—

- The site is isolated from waterways

- Knotweed fragments can and will be collected

- Part of an integrated removal strategy

Generally, mowing is not an acceptable form of knotweed treatment, and if you’re interested in mechanical treatments, we suggest you pick from the forms above. Of which, mechanical treatments are often the most ecologically friendly treatments that involve the lowest amount of secondary poisoning18, or other indirect effects of the treatment on local wildlife. The landscape of greater Vermont is mostly agriculturally active and fertile, so when it comes to preserving the green landscapes we love most, mechanical solutions are most always preferred to any of the latter.

Chemical Treatment

Approaching knotweed treatment from a chemical standpoint can be daunting, especially for the homeowner. In this section, we’ll cover the main accepted chemical treatments without spending too much time on the variation within the chemicals used. If you’re more interested in learning more about the different chemicals, check out this source on the chemicals of knotweed treatment.

Foliar Application

This type of treatment aims to treat the knotweed leaves alone. Foliar treatment is typically done late in the year, we suggest between late August and July. The herbicide chosen should be sprayed over the leaf section, during a calm and dry weather period to avoid contaminating neighboring fauna. Avoid overspray, but there should be enough spray to make the leaves damp. If done correctly, this form of chemical treatment could act as a good start for further knotweed treatments.

“A high-volume foliar application is the best method to treat knotweed that has not been cut19.”

Cut-Stem Application

This strategy involves painting herbicides directly onto cut knotweed. It works like foliar application but is more precise and targeted. It requires a less herbicide and can be better applied to areas with mixed vegetation.

Stem Injection

Injection toolkits are widely produced and made available for local treatment efforts20. The toolkit involves a special injection tool that takes advantage of the hollow knotweed stems, introducing herbicide directly to the plan tissue. The method is very targeted and allows for systematic removal with precise injections. It also reduces the amount of environmental exposure to herbicides, although there are still risks of runoff. The process is labor intensive, and restricted to mature plants, which is why it’s not suggested for smaller patches.

Chemical Contingencies

There are a few important things to be noted when considering chemical treatment. For all the chemical treatments above, timing is of the essence. The treatments themselves won’t work if you fail to catch the plants during the current time of year. That time is late season translocation21 when the plants are transferring their nutrients to the rhizomes. If timed right, the herbicides become integrated to the plant mass during this window and transferred to the rhizomes, effecting killing the plants from its inner source.

Unlike mechanical treatments, chemical approaches follow established regulations. In Vermont we have our own state-regulations. We broke down this extensive list in this safety & regulations source.

Another risk to be wary of when considering chemical treatment is target-runoff. This is when the treatment zone is either mis-addressed or a small number of herbicides are transferred to organisms outside of the targeted ones. The best way to prevent these chemical transfers is through general safe practices that we assembled in this safe practices source.

Integrated Treatments

Oftentimes using both mechanical and chemical treatments together works well for thorough efforts of knotweed treatment. This strategy involves choosing a method from both categories that fits with your plot of knotweed—is it large, overgrown, near a garden or populated space? Ask yourself these questions before you start your own treatment.

A multi-year strategy is used for most integrated treatments, involving both cutting and chemical treatment of the plants. We’ll outline a brief overview of what this may look like below.

Spring—Wait for early spring knotweed growth (1-2 feet). Map the plot using your phone or camera. Cut all the knotweed down to 2-3 inches from the ground.

Summer—Let the cut knotweed regrow for a final cut during this peak growing period. You may also choose other forms of mechanical disturbance like solarization or excavation based on your commitment level.

Early Fall—Apply herbicide to the previously cut knotweed.

Late Fall—Evaluate your progress and map the plot for the following year.

Like any knotweed treatment, these efforts need to be sustained along the suggested 3–5-year period. What the community has found is that these integrated approaches are better at targeting knotweed patches without harming nearby natives.

Emerging Treatments

Knotweed control is a space of plant and soil science that is constantly being studied. And with this, there are often many new technologies and strategies proposed. All the strategies below come from smaller sample sizes, and we haven’t seen enough of them to suggest them for your own use. That being said, they are interesting and intuitive ways that scientists and farmers have found to treat the invasive knotweed and will likely play a role in future treatment protocols.

Biocontrol

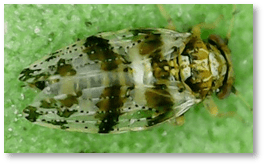

This form of treatment involves using other living organisms to treat knotweed. This is a clean form of treatment and if done right could provide easier treatment for homeowners who may be unaware of where to start. This sap-sucking psyllid aphalara itadori is a member of a plant-feeding family of insects that in this case, eat knotweed! The government has recently22 permitted the use of this insect in some test areas for study. Early results have shown that the insects are highly efficient at limiting growth of knotweed laterally but fall short in fully eradicating the plant. Within this field there is also work being done on ecological damping23—the effort to reduce environmental disturbances (often chemically induced) to improve ecosystem stability.

For farmers, repeated grazing by goats, sheep, or cattle on young shoots has been observed as an effective knotweed treatment24. What we’ve found in this strategy are similar results to mowing. If done well with little to no knotweed biomass left untreated, this could be an eco-friendly approach.

Fungus have also recently arisen as a form of treatment. Pathogens have been intentionally introduced to the knotweed through soil and plant tissue that has shown positive signs of knotweed aversion over several months. What recent studies have shown on mycosphaerella polygoni-cuspidati25, a fungal leaf-spot pathogen, suggest that the fungi are able to eradicate the leaves and stem structure but struggle to approach rhizomic development.

Other Methods

Commonly seen in the UK, the use of a root barrier/membrane has been an effective way to control knotweed growth. But by inserting a barrier around the knotweed root system, the plant loses its ability to expand and in theory will eventually die off. This treatment style is a longer form approach, and there hasn’t been convincing evidence of its ability to eradicate the plant fully.

The use of electricity is another common option across seas. “Electrothermal26” weed control is what they call it, and it involves shocking the plant and soil regions, targeting the rhizomes and other plant biomass in the area for localized death. This method is extremely limited in use, and although it has been shown to be advantageous, chemical free, and environmentally friendly, it’s extremely expensive and a labor-intensive process.

Treating Yourself

Now, with all the information above, you should be well equipped to tackle your own plot of knotweed. You now know the basics of knotweed growth, physiology, and behavior along with the methods we’ve seen most effective at treating it. We suggest starting with a mechanical treatment—try your hand (literally) at digging or cutting knotweed. Observe how it regrows and how well your able to tackle it on your own. Start this way for a year or two and if you see little progress, check out our resource on the chemicals of knotweed treatment along with the strategies discussed here. We wish you luck and hope to see your knotweed-free backyard in the upcoming years!

Footnotes

- This recent blog post ushers the importance of “choosing your battles” in invasives control. (Lavoie, 2025)

- Article published by the Agency of Agriculture and Food Market of Vermont on knotweed. (Japanese Knotweed in Vermont | Agency of Agriculture Food and Markets)

- Japanese knotweed article out of Penn State. (Japanese Knotweed)

- Herbaceous perennial plants are non-woody plants that typically have soft green stems. Perennial nature means that they go through a full growth each year with root systems that allow them to continue in future years.

- Plant stem structure is often broken up to apical and lateral stems. Apical is usually the original stem that emerged from the ground, where lateral stems branch off from this central, thicker stem.

- Hybridization is the process of two separate (plant) species mixing and becoming one. This is often due to proximity and evolutionary pressures. (Kang, 2023)

- Clonal species in plants are those that reproduce asexually (alternative to sexual reproduction) resulting in offspring that are genetically identical and/or connected to the parent.

- Rhizomes are stems that grow horizontally instead of upright. In knotweed and other clonal species, rhizomes are the site of asexual reproduction (how future knotweed comes to life). (Rhizomes)

- Herbicides are chemical or biological substances that are used to kill or mediate plant species. Commonly used to treat weeds. Learn more about the chemicals of knotweed treatment. Check out this article on dormancy— (Jolly, 2020)

- When a change at the level of the food chain leads to sequential changes at other levels. Think about if all the chickens in the world caught disease.

- A measure of how cloudy or opaque a body of water (or fluid) is. An increase in turbidity makes it harder for marine life to see and survive.

- Biocontrol is the use of other organic materials, usually microorganisms or other local species, to mediate some sort of growth or predatory behavior. For example, greenhouse managers use wasps as a form of biocontrol to mediate fungal growth on their plants.

- This article covers some best practices in knotweed (mechanical) control methods and how it could go wrong. (Control Methods)

- This research group out of Washington state studied several different methods of treatment. (Controlling Invasive Knotweed)

- Commercial knotweed treatments are most popular in the UK. This source is one of the most established groups. (Excavation Services)

- Root assassins are long serrated shovels that work well for breaking up dirt and rhizome material when excavating. (Erler, 2019)

- A polymeric (synthetic) layer, impermeable, that is used to control migrant of liquids and plant life. There are many variants, all described in this source— (Whittle, 2002)

- When chemical (often herbicidal) treatment runoff affects local species. Learn more here— (Secondary Poisoning)

- This study found that foliar treatment is the best for untreated knotweed, suggesting it as the best way to start an integrated approach. (Roadside Vegetation Management)

- (Stem Injector Kit)

- Time of the year (typically August-September) when rhizomic perennial plants move water, minerals, and sugars through the tissue system to storage underground.

- This study out of Cornell was one of the first to use biocontrol to treat knotweed. (Beauregard, 2015)

- Article on the importance of ecological stability, coining the term “ecological damping.” (Parshad, 2016)

- The use of animal grazing in knotweed treatments. (Knotweed, J.)

- This fungal species is explained in this article to have a great effect on knotweed. (Evaluating the Mycoherbicides)

- This form of treatment uses heat and electricity to literally shock knotweed to death. (JapKnot)

- Beauregard, M., Black, K., Parshad, R., & Quansah, E. (2015). Biological control via “ecological” damping: An approach that attenuates non-target effects. ArXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1502.02010

- Control Methods | Pierce Conservation District, WA. (2025). Piercecd.org. https://piercecd.org/184/Control-Methods

- Controlling Invasive Knotweed and Restoring Impacted Habitat on an Organic Farm in Western Washington State. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2025, from https://www.oxbow.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Knotweed-Control-Writeup.pdf

- Erler, C. T. (2019, July 25). Root Assassin Shovel: Product Review – Gardening Products Review. Gardening Products Review. https://gardeningproductsreview.com/root-assassin-shovel-review/

- Evaluating the mycoherbicide potential of a leaf-spot pathogen against Japanese knotweed. (n.d.). CABI.org. https://www.cabi.org/projects/evaluating-the-mycoherbicide-potential-of-a-leaf-spot-pathogen-against-japanese-knotweed/

- EXCAVATION SERVICES – Japanese Knotweed Ltd. (2025, November 14). Japanese Knotweed Ltd. https://japaneseknotweed.co.uk/treatment-and-removal/eradication/#full

- Japanese Knotweed. (n.d.). Penn State Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/japanese-knotweed

- Japanese Knotweed in Vermont | Agency of Agriculture Food and Markets. (2023). Vermont.gov. https://agriculture.vermont.gov/japanese-knotweed-vermont

- JapKnot. (2025, January 22). Japanese Knotweed Plus. Japanese Knotweed Plus. https://japaneseknotweedplus.co.uk/innovative-solutions-for-japanese-knotweed-treatment/

- Jolly, W. (2020, April 30). Dormant Japanese Knotweed [A Complete Guide For 2022]. Knotweed Help. https://www.knotweedhelp.com/japanese-knotweed-guide/dormant-knotweed/

- Kang, M. (2023). Hybridization (Botany) | EBSCO. EBSCO Information Services, Inc. | Www.ebsco.com. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/agriculture-and-agribusiness/hybridization-botany

- Knotweed, J. (n.d.). JAPANESE KNOTWEED GOOD PRACTICE MANAGEMENT. https://nnnsi.org/assets/NNNSI/JKW-management.pdf

- Lavoie, C. (2025, August 15). Japanese Knotweed: Choosing Your Battles. Laidback Gardener. https://laidbackgardener.blog/2025/08/15/japanese-knotweed-choosing-your-battles/

- Parshad, R. D., Quansah, E., Black, K., & Beauregard, M. (2016). Biological control via “ecological” damping: An approach that attenuates non-target effects. Mathematical Biosciences, 273, 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2015.12.010

- Rhizomes. (n.d.). Rhizomes. https://www.uaex.uada.edu/yard-garden/resource-library/plant-week/Rhizomes-12-06-2019-Ark.aspx

- Roadside Vegetation Management Managing Japanese Knotweed and Giant Knotweed on Roadsides. (n.d.).

- Secondary Poisoning of Wildlife. (n.d.). https://opm.azda.gov/Assets/PDFDocuments/SecondaryPoisoningFlyerFinal.pdf

- Stem Injector Kit. (2025). Green Shoots Online. https://www.greenshootsonline.com/products/stem-injector-kit-for-tough-stems?srsltid=AfmBOorKX4BYjXqIsUJwrtYDhT6e–3vQkxldpNvpTP0iourcE5dFNBJ

- Whittle, A., & Ling, H-I. (2002). Geomembrane – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Www.sciencedirect.com. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/materials-science/geomembrane